A SYSTEM FOR WRITING: How an Unconventional Approach to Note-Making Can Help You Capture Ideas, Think Wildly, and Write Constantly A Zettelkasten Primer by Bob Doto (2024)

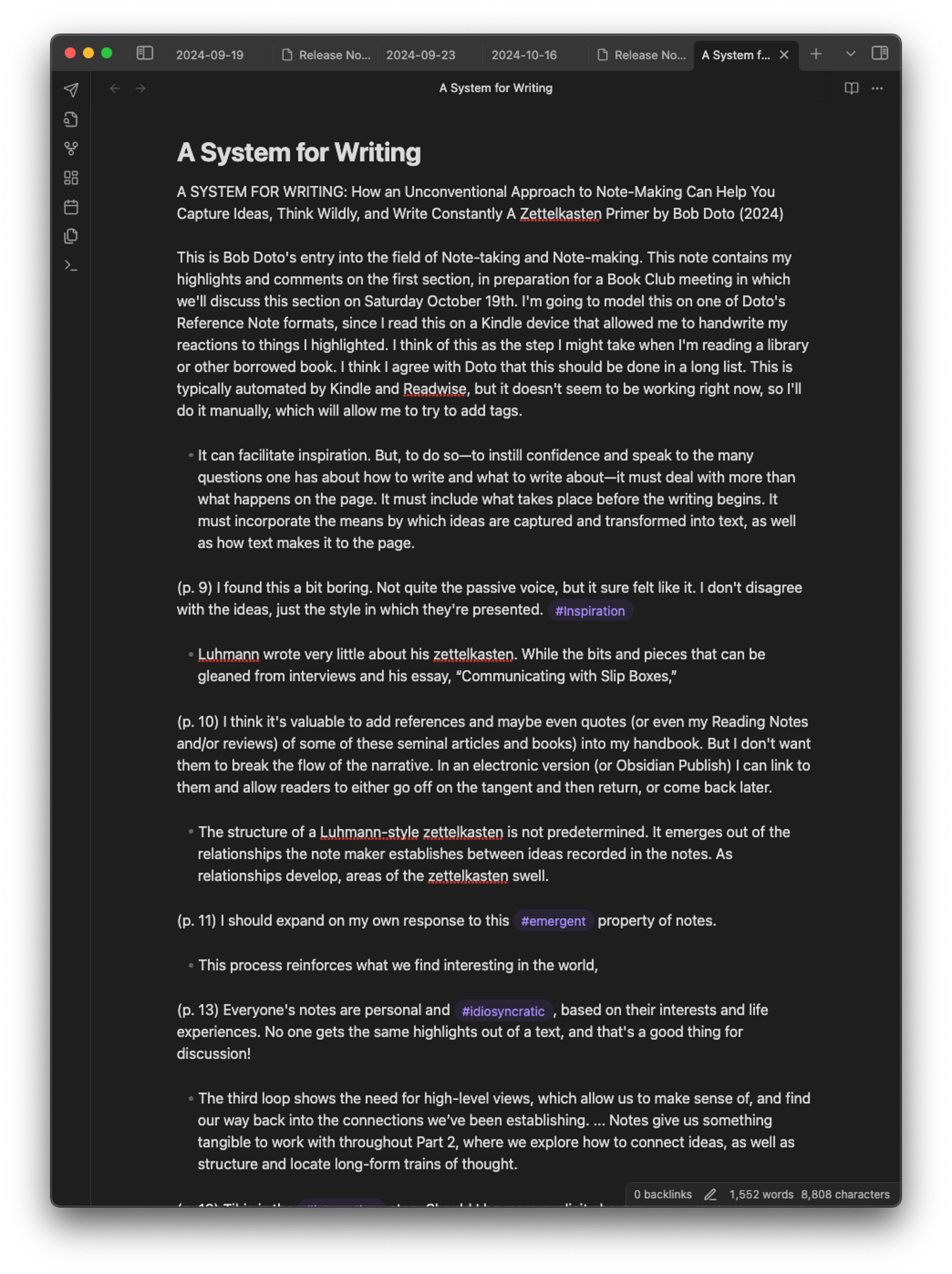

This is Bob Doto's entry into the field of Note-taking and Note-making. This note contains my highlights and comments on the first section, in preparation for a Book Club meeting in which we'll discuss this section on Saturday October 19th. I'm going to model this on one of Doto's Reference Note formats, since I read this on a Kindle device that allowed me to handwrite my reactions to things I highlighted. I think of this as the step I might take when I'm reading a library or other borrowed book. I think I agree with Doto that this should be done in a long list. This is typically automated by Kindle and Readwise, but it doesn't seem to be working right now, so I'll do it manually, which will allow me to try to add tags.

It can facilitate inspiration. But, to do so—to instill confidence and speak to the many questions one has about how to write and what to write about—it must deal with more than what happens on the page. It must include what takes place before the writing begins. It must incorporate the means by which ideas are captured and transformed into text, as well as how text makes it to the page.

(p. 9) I found this a bit boring. Not quite the passive voice, but it sure felt like it. I don't disagree with the ideas, just the style in which they're presented. #Inspiration

Luhmann wrote very little about his zettelkasten. While the bits and pieces that can be gleaned from interviews and his essay, “Communicating with Slip Boxes,”

(p. 10) I think it's valuable to add references and maybe even quotes (or even my Reading Notes and/or reviews) of some of these seminal articles and books) into my handbook. But I don't want them to break the flow of the narrative. In an electronic version (or Obsidian Publish) I can link to them and allow readers to either go off on the tangent and then return, or come back later.

The structure of a Luhmann-style zettelkasten is not predetermined. It emerges out of the relationships the note maker establishes between ideas recorded in the notes. As relationships develop, areas of the zettelkasten swell.

(p. 11) I should expand on my own response to this #emergent property of notes.

This process reinforces what we find interesting in the world,

(p. 13) Everyone's notes are personal and #idiosyncratic, based on their interests and life experiences. No one gets the same highlights out of a text, and that's a good thing for discussion!

The third loop shows the need for high-level views, which allow us to make sense of, and find our way back into the connections we’ve been establishing. ... Notes give us something tangible to work with throughout Part 2, where we explore how to connect ideas, as well as structure and locate long-form trains of thought.

(p. 13) This is the #integration step. Should I be more explicit about the ways that elements of the slipbox map to steps in the process?

the less common “source note”

(p. 15) Aw shucks; he seems to have read my book! I'm going to keep calling them Source Notes because they're notes about sources.

“The mind is for having ideas, not holding them.” ... Engaging with the slip box should feel exciting, not anxiety-producing. By giving your ideas a place to land, an inbox helps alleviate some of the potential anxiety that initially comes from working non-hierarchically

(pp. 19, 22) This quote from David Allen's Getting Things Done is a good way to express this. Doto continues later to channel Allen's idea that "unfinished business" creates #anxiety and distraction.

Stage Your Fleeting Notes in an Inbox

(p. 21) The idea of an #Inbox for fleeting and Source Notes is a really good idea, as is the advice to set a schedule for reviewing it and adding a "Sleeping" folder.

accountability. There’s a lot at stake when putting thoughts into words.

(p. 29) I wonder whether putting it like this increases or decreases #anxiety ?

writing, even in the form of short notes, helps us understand what we think we know.

(p. 29) I think this is a more positive way of expressing the previous point. And it fits in the Luhmann and Ahrens tradition that #WritingisThinking.

Making a reference note from your journal

(p. 43) Full-text search allows a tool like Obsidian to facilitate finding ideas in #DailyNotes. I think this is a really valuable method for reviewing how my thoughts on a particular topic have changed over time. Also how they relate to other ideas, since the essay-length Daily Notes can give me clues about the ways these ideas develop in a train of thought and also whether there are any related ideas that qualify or add nuance.

When you have an agenda, all forms of media can be mined for inspiration and information.

(p. 45) And everybody has an #agenda, whether they're aware of it or not.

The stuff that gets under your skin can be incredibly motivating.

(p. 45) My entire interest in and approach to history might be summed up in those words! #contrarian

By capturing his marginalia on slips of paper, Luhmann was able to store his captures inside his zettelkasten,

(pp. 47-48) Can't #link notes if they can't see each other!

Write, underline, or otherwise indicate in the margins interesting passages you encountered while reading. Go back and pull what interests you into a reference note.

(p. 48) This is basically how I tell my students to process their textbooks. The notes are what they'll bring to discussion, rather than trying to flip or scroll through the text to find what they need in realtime.

A main note works best when the thought contained inside has been pared down to its essentials.

(p. 56) This is also an important element in #distilling ideas. The challenge is to separate these thoughts into something more #atomic -- although I agree with Bob that there's probably been a bit too much obsessing over atomicity.

A title acts as a condensed thesis summing up the content of the idea stored in the note. It should be a declarative statement rather than a descriptor. “Not all apples are edible” is a better title than “Apples and edibility.” The former tells the note maker what’s being said inside the note while the latter hints at the topic to which the idea might be speaking.

(p. 57) A useful distinction and a good idea: #DescriptiveTtitles

bring the quoted passage into your main note.

(p. 57) Even if you're paraphrasing (which I recommend UNLESS the quote is so valuable you'll use it in your output), you should still cite the source so you can review the context in which it appears and then cite it in your output.

track how and where an idea has been used in your writing.

(p. 58) This is valuable advice for anyone who is going to write more than just one thing ever! As he mentions later, we can read our own stuff as if it was written by someone else, because it was! #self-reference

folgezettel ... a permanent identity that can be referenced regardless of any changes made to the note’s content.

(p. 58) I'm still not sure how I feel about these #UniqueIDs in a digital setting. I thought we had already established that note content shouldn't be edited in a quest for the perfect #evergreen note.

If the idea relates to another already networked in your slip box, either rewrite it to speak directly to the other idea, or reference the previously captured idea and state why you’re making the connection.

(p. 59) Explaining the connection helps me understand it fully and also helps #future-me avoid wondering what (the hell!) I was thinking when I made the note.

Next, consider whether the idea speaks to any other ideas stored in your zettelkasten

(p. 59) I used to call these #SidewaysLinks

Say something about the fact.

(p. 66) This is the whole point in the long run. Should it be done on that particular note or on one immediately "after" it?

developing ideas in light of others already stored therein

(p. 70) I was stumped where he was going in this section, but I think he's addressing the question of whether to force the #linking of a new note to one that already exists in the slipbox.

Wrong ideas, if given context, can serve not only as counter arguments to be incorporated into your writing, but can be used to show how your own beliefs have shifted over time.

(p. 70) I really dislike the idea that there are "Wrong" ideas. They should develop and be modified ( #evolve ) over time.

Take Schmidt’s words to heart.

(p. 71) We're all, obviously, responding to and to some extent leaning on these previous ideas. I'm not sure the most effective way to express that, necessarily, is to build them into the narrative in this way.

Mine are in slightly different form on another platform (and to date I haven't transcribed them all from the margins of my physical book), but they're also available digitally here: https://hypothes.is/users/chrisaldrich?q=url%3Aurn%3Ax-pdf%3A231323658d79d9bdf946e1cfbe01e500

Thanks for sharing your highlights. I really enjoyed this book, even though it came several years too late for me, so I’d already worked out a very similar system of my own!

You are correct: “source note” is by far the best term.